Overview

Most applications are built by layering one data model on top of another. For each layer, the key question is: how is it represented in terms of the next-lower layer?

Example:

1. As an application developer, you look at the real world (in which there are people, organizations, goods, actions, money flows, sensors, etc.) and model it in terms of objects or data structures, and APIs that manipulate those data structures. Those structures are often specific to your application.

2. When you want to store those data structures, you express them in terms of a general-purpose data model, such as JSON or XML documents, tables in a relational database, or a graph model.

3. The engineers who built your database software decided on a way of representing that JSON/XML/relational/graph data in terms of bytes in memory, on disk, or on a network. The representation may allow the data to be queried, searched, manipulated, and processed in various ways.

4. On yet lower levels, hardware engineers have figured out how to represent bytes in terms of electrical currents, pulses of light, magnetic fields, and more.

Relational Models VS Document Model

SQL, the best-know data model today, based on the relational model proposed by Edgar Codd in 1970: data is organized in to relations (called tables in SQL), where each relation is an unordered collection of tuples (rows in SQL).

The roots of relational databases lie in business data processing, the use cases appear today: transaction processing (entering sales or banking transactions, stock-keeping in warehouses) and batch processing (customer invoicing, payroll, reporting).

The Birth of NoSQL

In the 2010s, NoSQL is the latest attempt to overthrow the relational model’s dominance. The driving force of NoSQL is:

- A need for greater scalability than relational databases can easily achieve, including very large datasets or very high write throughput

- A widespread preference for free and open source software over commercial database products

- Specialized query operations that are not well supported by the relational model

- Frustration with the restrictiveness of relational schemas, and a desire for a more dynamic and expressive data model

The Object-Relational Mismatch

Most application development today is done in object-oriented programming languages, which leads to a common criticism of the SQL data model: if data is stored in relational tables, an awkward translation layer is required between the objects in the application code and the database model of tables, rows, and columns. The disconnect between the models is sometimes called an impedance mismatch.

Object-relational mapping (ORM) frameworks like ActiveRecord and Hibernate reduce the amount of boilerplate code required for this translation layer, but they can’t completely hide the differences between the two models.

Example:

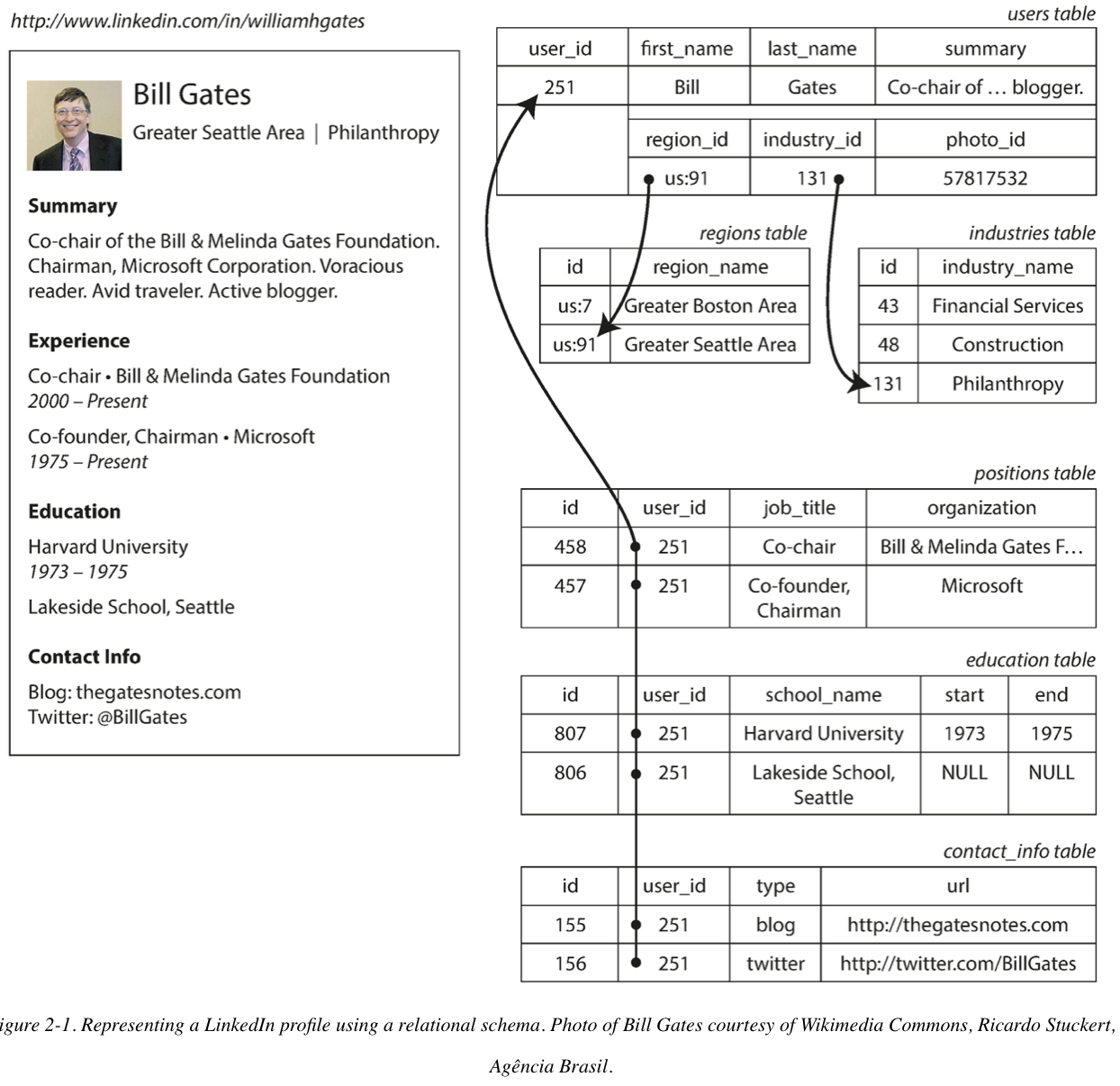

The resume contains a one-to-many relationship, which can be represented in:

- the most common normalized representation is to put positions, education, and contact information in separate tables, with a foreign key reference to the users table

- Later versions of the SQL standard added support for structured datatypes and XML data; this allowed multi-valued data to be stored within a single row, with support for querying and indexing inside those documents

- encode jobs, education, and contact info as a JSON or XML document, store it on a text column in the database, and let the application interpret its structure and content. In this setup, you typically cannot use the database to query for values inside that encoded column.

For data structure like a resume, which is mostly a self-contained document, a JSON representation can be quite appropriate. JSON has the appeal of being much simpler than XML. Document-oriented database like MongoDB, RethinkDB, CouchDB, and Expresso support this data model.

The JSON representation has better locality than the multi-table schema in Figure 2-1. If you want to fetch a profile in the relational example, you need to either perform multiple queries (query each table by user_id) or perform a messy multi-way join between the users table and its subordinate tables. In the JSON representation, all the relevant information is in one place, and one query is sufficient.

Many-to-One and Many-to-Many Relationships

If the user interface has free-text fields for entering the region and the industry, it makes sense to store them as plain-text strings. But there are advantages to having standardized lists of geographic regions and industries, and letting users choose from a drop-down list or autocompleter:

Consistent styleandspelling across profilesAvoiding ambiguity(e.g., if there are several cities with the same name)- Ease of updating—the name is stored in only one place, so it is

easy to update across the boardif it ever needs to be changed (e.g., change of a city name due to political events) Localization support—when the site is translated into other languages, the standardized lists can be localized, so the region and industry can be displayed in the viewer’s languageBetter search—e.g., a search for philanthropists in the state of Washington can match this profile, because the list of regions can encode the fact that Seattle is in Washington (which is not apparent from the string “Greater Seattle Area”)

The advantage of using an ID is that because it has no meaning to humans, it never needs to change: the ID can remain the same, even if the information it identifies changes. That incurs write overheads, and risks inconsistencies (where some copies of the information are updated but others aren’t). Removing such duplication is the key idea behind normalization in databases.

In relational databases, it’s normal to refer to rows in other tables by ID, because joins are easy. In document databases, joins are not needed for one-to-many tree structures, and support for joins is often weak

Are document Databases Repeating History?

Various solutions were proposed to solve the limitations of the hierarchical model. The two most prominent were the relational model (which became SQL, and took over the world) and the network model (which initially had a large following but eventually faded into obscurity).

Network Model

The network model was standardized by a committee called the Conference on Data Systems Languages (CODASYL) and implemented by several different database vendors; it is also known as the CODASYL model.

The CODASYL model was a generalization of the hierarchical model. In the tree structure of the hierarchical model, every record has exactly one parent; in the network model, a record could have multiple parents.

The links between records in the network model were not foreign keys, but more like pointers in a programming language (while still being stored on disk). The only way of accessing a record was to follow a path from a root record along these chains of links. This was called an access path.

A query in CODASYL was performed by moving a cursor through the database by iterating over lists of records and following access paths. If a record had multiple parents (i.e., multiple incoming pointers from other records), the application code had to keep track of all the various relationships. Even CODASYL committee members admitted that this was like navigating around an n-dimensional data space.

The problem was that they made the code for querying and updating the database complicated and inflexible. With both the hierarchical and the network model, if you didn’t have a path to the data you wanted, you were in a difficult situation. You could change the access paths, but then you had to go through a lot of handwritten database query code and rewrite it to handle the new access paths. It was difficult to make changes to an application’s data model.

Relational Model

Relational Model lay out all the data in the open: a relation (table) is simply a collection of tuples (rows), and that’s it. There are no labyrinthine nested structures, no complicated access paths to follow if you want to look at the data. You can read any or all of the rows in a table, selecting those that match an arbitrary condition. You can read a particular row by designating some columns as a key and matching on those. You can insert a new row into any table without worrying about foreign key relationships to and from other tables.

In a relational database, the query optimizer automatically decides which parts of the query to execute in which order, and which indexes to use. If you want to query your data in new ways, you can just declare a new index, and queries will automatically use whichever indexes are most appropriate.

A key insight of the relational model was this: you only need to build a query optimizer once, and then all applications that use the database can benefit from it.

Comparison to document databases

Document databases reverted back to the hierarchical model in one aspect: storing nested records within their parent record rather than in a separate table.

When it comes to representing many-to-one and many-to-many relationships, relational and document databases are not fundamentally different: in both cases, the related item is referenced by a unique identifier, which is called a foreign key in the relational model and a document reference in the document model. That identifier is resolved at read time by using a join or follow-up queries. To date, document databases have not followed the path of CODASYL.

Relational VS Document Databases Today

The main arguments in favor of the document data model are schema flexibility, better performance due to locality, and that for some applications it is closer to the data structures used by the application. The relational model counters by providing better support for joins, and many-to-one and many-to-many relationships.

Which data model leads to simpler application code?

If the data in your application has a document-like structure (i.e., a tree of one-to-many relationships, where typically the entire tree is loaded at once), then it’s probably a good idea to use a document model. The relational technique of shredding—splitting a document-like structure into multiple tables can lead to cumbersome schemas and unnecessarily complicated application code.

The document model has limitations: ex, you cannot refer directly to a nested item within a document, but instead you need to say something like “the second item in the list of positions for user 251” (much like an access path in the hierarchical model). However, as long as documents are not too deeply nested, that is not usually a problem.

The poor support for joins in document databases may or may not be a problem, depending on the application. For example, many-to-many relationships may never be needed in an analytics application that uses a document database to record which events occurred at which time.

For highly interconnected data, the document model is awkward, the relational model is acceptable, and graph models are the most natural.

Schema flexibility in the document model

schema-on-read: the structure of the data is implicit, and only interpreted when the data is readschema-on-write: the traditional approach of relational databases, where the schema is explicit and the database ensures all written data conforms to it

Schema-on-read is similar to dynamic (runtime) type checking in programming languages, whereas schema-on-write is similar to static (compile-time) type checking.

The schema-on-read approach is advantageous if the items in the collection don’t all have the same structure for some reason (i.e., the data is heterogeneous) because:

- There are many different types of objects, and it is not practicable to put each type of object in its own table.

- The structure of the data is determined by external systems over which you have no control and which may change at any time.

Data locality for queries

A document is usually stored as a single continuous string, encoded as JSON, XML, or a binary variant thereof (such as MongoDB’s BSON). If your application often needs to access the entire document (for example, to render it on a web page), there is a performance advantage to this storage locality. If data is split across multiple tables, multiple index lookups are required to retrieve it all, which may require more disk seeks and take more time.

The locality advantage only applies if you need large parts of the document at the same time. The database typically needs to load the entire document, even if you access only a small portion of it, which can be wasteful on large documents. On updates to a document, the entire document usually needs to be rewritten—only modifications that don’t change the encoded size of a document can easily be performed in place. For these reasons, it is generally recommended that you keep documents fairly small and avoid writes that increase the size of a document. These performance limitations significantly reduce the set of situations in which document databases are useful.

Query Languages for Data

SQL is a declarative query language, whereas IMS and CODASYL queried the database using imperative code.

An imperative language tells the computer to perform certain operations in a certain order.

In a declarative query language, like SQL or relational algebra, you just specify the pattern of the data you want—what conditions the results must meet, and how you want the data to be transformed (e.g., sorted, grouped, and aggregated)—but not how to achieve that goal. It is up to the database system’s query optimizer to decide which indexes and which join methods to use, and in which order to execute various parts of the query.

The SQL example doesn’t guarantee any particular ordering, and so it doesn’t mind if the order changes. But if the query is written as imperative code, the database can never be sure whether the code is relying on the ordering or not. The fact that SQL is more limited in functionality gives the database much more room for automatic optimizations.

Declarative languages often lend themselves to parallel execution. Imperative code is very hard to parallelize across multiple cores and multiple machines, because it specifies instructions that must be performed in a particular order. Declarative languages have a better chance of getting faster in parallel execution because they specify only the pattern of the results, not the algorithm that is used to determine the results.

MapReduce Querying

MapReduce is a programming model for processing large amounts of data in bulk across many machines.

MapReduce is neither a declarative query language nor a fully imperative query API, but somewhere in between: the logic of the query is expressed with snippets of code, which are called repeatedly by the processing framework. It is based on the map (also known as collect) and reduce (also known as fold or inject) functions that exist in many functional programming languages.

Graph-Like Data Models

A graph consists of two kinds of objects: vertices (also known as nodes or entities) and edges (also known as relationships or arcs). Many kinds of data can be modeled as a graph.

Graphs are not limited to such homogeneous data: an equally powerful use of graphs is to provide a consistent way of storing completely different types of objects in a single datastore. For example, Facebook maintains a single graph with many different types of vertices and edges: vertices represent people, locations, events, checkins, and comments made by users; edges indicate which people are friends with each other, which checkin happened in which location, who commented on which post, who attended which event, and so on.

Property Graphs

Each vertex consists of:

- A unique identifier

- A set of outgoing edges

- A set of incoming edges

- A collection of properties (key-value pairs)

Each edge consists of:

- A unique identifier

- The vertex at which the edge starts (the tail vertex)

- The vertex at which the edge ends (the head vertex)

- A label to describe the kind of relationship between the two vertices

- A collection of properties (key-value pairs)

The important aspects of this model:

- Any vertex can have an edge connecting it with any other vertex. There is no schema that restricts which kinds of things can or cannot be associated.

- Given any vertex, you can efficiently find both its incoming and its outgoing edges, and thus traverse the graph—i.e., follow a path through a chain of vertices—both forward and backward.

- By using different labels for different kinds of relationships, you can store several different kinds of information in a single graph, while still maintaining a clean data model.

The Cypher Query Language

Cypher is a declarative query language for property graphs.

Graph Queries in SQL

If we put graph data in a relational structure, can we also query it using SQL? The answer is yes, but with some difficulty. In a relational database, you usually know in advance which joins you need in your query. In a graph query, you may need to traverse a variable number of edges before you find the vertex you’re looking for—that is, the number of joins is not fixed in advance.

Triple-Stores and SPARQL

The triple-store model is mostly equivalent to the property graph model, using different words to describe the same ideas. In a triple-store, all information is stored in the form of very simple three-part statements: (subject, predicate, object). For example, in the triple (Jim, likes, bananas), Jim is the subject, likes is the predicate (verb), and bananas is the object.

SPARQL is a query language for triple-stores using the RDF data model.

Graph Databases Compared to the Network Model

Are graph databases the second coming of CODASYL in disguise?

NO.

- In

CODASYL, a database had aschemathat specified which record type could be nested within which other record type. In agraphdatabase, there isnosuch restriction: any vertex can have an edge to any other vertex. This gives much greater flexibility for applications to adapt to changing requirements. - In

CODASYL, theonly way to reach a particular record was to traverse one of the access pathsto it. In agraphdatabase, you can referdirectly to any vertex by its unique ID, or you canuse an index to find vertices with a particular value. - In

CODASYL, thechildren of a record were an ordered set, so the database had to maintain that ordering (which had consequences for the storage layout) and applications that inserted new records into thedatabase had to worry about the positionsof the new records in these sets. In agraphdatabase, vertices and edges arenot ordered(you can only sort the results when making a query). - In

CODASYL, all queries wereimperative,difficult to write and easily brokenby changes in the schema. In agraphdatabase, you can write your traversal in imperative code if you want to, but most graph databases also supporthigh-level, declarative query languagessuch as Cypher or SPARQL.

Datalog

Datalog’s data model is similar to the triple-store model, generalized a bit. Instead of writing a triple as (subject, predicate, object), we write it as predicate(subject, object).

Summary

Documentdatabases target use cases where data comes inself-containeddocuments andrelationshipsbetween one document and another arerare.Graphdatabases go in the opposite direction, targeting use cases where anything ispotentially relatedto everything.

One thing that document and graph databases have in common is that they typically don’t enforce a schema for the data they store, which can make it easier to adapt applications to changing requirements. However, your application most likely still assumes that data has a certain structure; it’s just a question of whether the schema is explicit (enforced on write) or implicit (assumed on read).

Reference

- https://learning.oreilly.com/library/view/-/9781491903063/ch02.html

Comments

Join the discussion for this article at here . Our comments is using Github Issues. All of posted comments will display at this page instantly.