Overview

Most applications today are data-intensive(compute-instensive). Raw CPU is rarely a limiting factor for these applications, bigger problems are using the amount of data.

Data-intensive typically built from standard building blocks that provide commonly needed functionality. ex:

- Store data which can find it again later – database

- Remember the result which can speed up reads – caches

- Search data by keyword or filter it – search indexes

- Send message to another process, to be handled asynchronously – stream processing

- Periodically crunch a large amount of accumulated data – batch processing

Many new tools for data storage and processing have merged in recent years. ex: datastores that are also used as a message queues(Redis), message queues with database-like durability guarantees(Apache Kafka). The boundaries between categories are becoming blurred.

When you combine several tools in order to provide a service, the service’s interface or application programming interface(API) usually hides those implementation details from clients. Now you’ve essentially created a new, special0purpose data system from smaller, general-purpose components. ex: cache will be correctly invalidated or updated on writes so that outside clients see consistent results.

When design a data system or service, you might have lots of tricky questions, ex:

- How do you ensure that the data remains correct and complete, even when things go wrong internally?

- How do you provide consistently good performance to clients, even when parts of your system are degraded?

- How do you scale to handle an increase in load?

- What does a good API for the service look like?

There are many factors that may have influence the design of a data system, including the skiils and experience of the people involved, legacy system dependencies, the timescale for delivery, the organization’s tolerance of different kinds of risk, regulatory constraints. etc.

But we will focus on reliable, scalability, maintainability for now.

- Reliability

- The system should continue to work

correctly(performing the correct function at the desired level of performance) even in the face ofadversity(hardware of software faults, and even human error).

- The system should continue to work

- Scalability

- As the system

grows(in data volume, traffic volume, or complexity), there should be reasonable ways of dealing with that growth.

- As the system

- Maintainability

- Over time, many different people will work on the system (engineering and operations, bbobth maintaining current behavior and adapting the system ot new use cases), and they should all be able to work on it

productively.

- Over time, many different people will work on the system (engineering and operations, bbobth maintaining current behavior and adapting the system ot new use cases), and they should all be able to work on it

Reliability

- The application performs the function that the user expected

- It can tolerate the user making mistakes or using the software in unexpected ways

- Its performance is good enough for the required use case, under the expected load and data volume

- The system prevents any unauthorized access and abuse

Things can go wrong are called faults, and systems that anticipate faults and can cope with them are called fault-tolerant or resilient. fault-tolerant suggests we could make a system tolerant of every possible kind of fault(which in reality is not feasible).

It is impossible to reduce the probability of a fault to zero, therefore it is usually best to design fault-tolerance mechanisms that prevent faults from causing failures. In such fault-tolerant systems, it can make sense to increase the rate of faults by triggering them deliberately, ex: randomly killing individual processes without warning. Many critical bugs are actually due to poor error handling. By deliberately inducing faults, you eunsure the fault-tolerance machinery is continually exercised and tested and will be handled correctly when they occur naturally. The Netflix Chaos Monkey is an example of this approach.

Hardware Faults

Hard disks crash, RAM becomes faulty, power grid has a blackout, someone unplugs the wrong network cable.

Hard disks are reported as having a mean time to failure(MTTF) of about 10 to 50 years. Thus, on a storage cluster with 10,000 disks, we should expect on average one disk to die per day. Our first response is usually to add redundancy to the individual hardware components in order to reduce the failure rate of the system. Disks may be set up in a RAID configuration, servers may have dual power supplies and hot-swappable CPUs, and datacenters may have batteries and diesel generators for backup power. When one component dies, the redundant component can take its place while the broken component is replaced.

Recently, redundancy of hardware components makes total failure of a single machine fairly rare, as long as you can restore a backup onto a new machine fairly quickly, the downtime in case of failure is not catastrophic in most applications.

There is a move toward systems that can tolerate the loss of entire machines, by using software fault-tolerance techniques in preference or in addition to hardware redundancy. advantages: a single-server system requires planned downtime if you need to reboot the machine (to apply operating system security patches, for example), whereas a system that can tolerate machine failure can be patched one node at a time, without downtime of the entire system

Software Faults

Software faults are harder to anticipate, because they are correlated across nodes, they tend to cause many more system failures than uncorrelated hardware faults. ex:

- A software bug that causes every instance of an application server to crash when given a particular bad input. For example, consider the leap second on June 30, 2012, that caused many applications to hang simultaneously due to a bug in the Linux kernel

- A runaway process that uses up some shared resource — CPU time, memory, disk space, or network bandwidth.

- A service that the system depends on that slows down, becomes unresponsive, or starts returning corrupted responses.

- Cascading failures, where a small fault in one component triggers a fault in another component, which in turn triggers further faults

Human Errors

HUmans design and build software systems, and the operators who keep the system running are also human.

Scalability

Consider the increased load: perhaps the system has grown from 10,000 concurrent users to 100,000 concurrent users, or from 1 million to 10 million. Perhaps it is processing much larger volumes of data than it did before.

Scalability used to describe the system’s ability to cope with increased load.

Describing Load

Load can be described with load parameters.

Example:

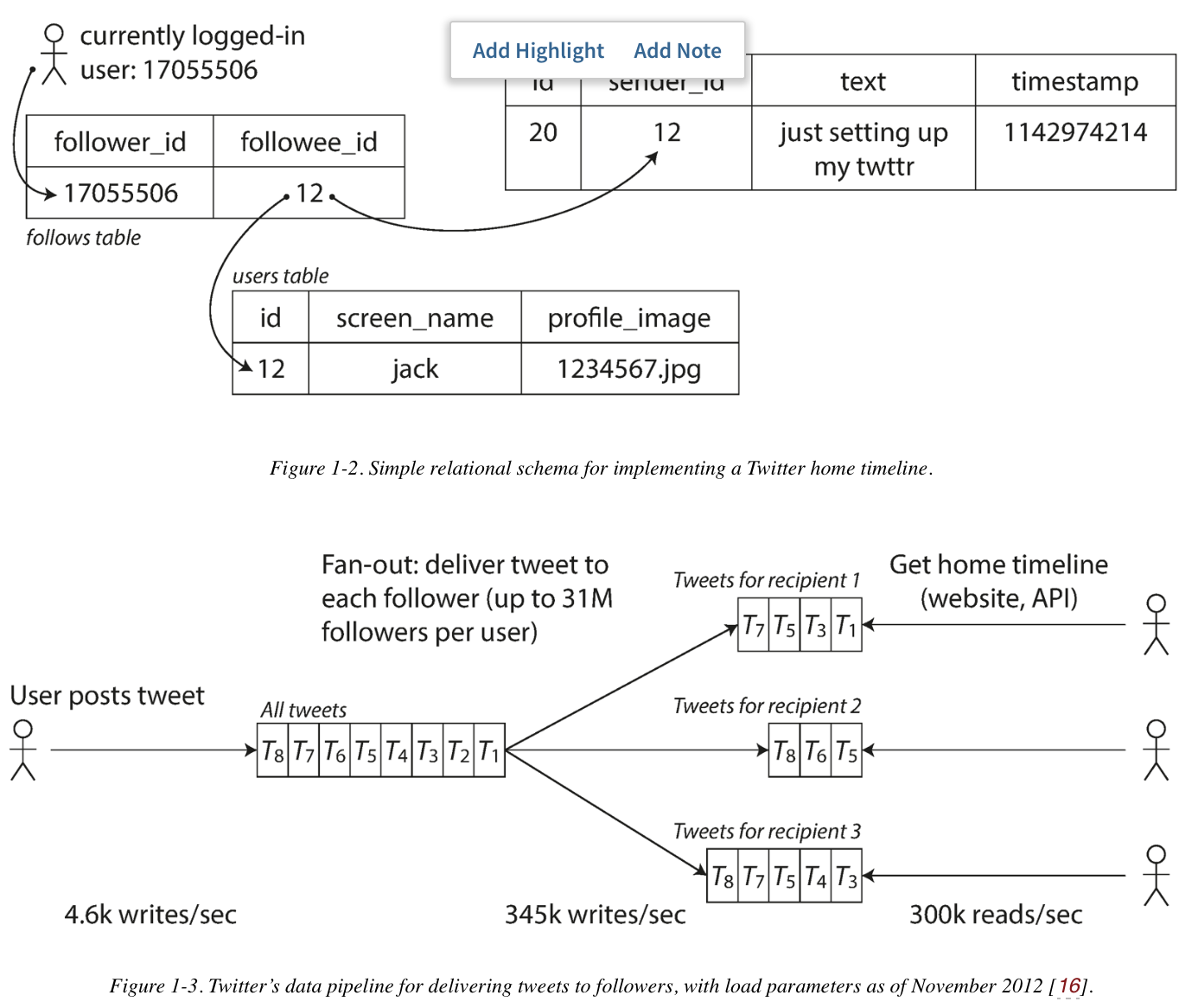

Take Twitter as an example, Twitter have two main operations:

- Post Tweet: A user can publish a new message to their followers (4.6k requests/sec on average, over 12k requests/sec at peak).

- home Timeline: A user can view tweets posted by the people they follow (300k requests/sec).

Two ways to implement the 2 operations:

1. Post tweet by simple inserts the new tweet into a global collection of tweets. When a user requests their home timeline, look up all the people they follow, find all the tweets for each of those users, and merge them (sorted by time)

2. When a user posts a tweet, look up all the people who follow that user, and insert the new tweet into each of their home timeline caches. The request to read the home timeline is then cheap, because its result has been computed ahead of time.

Previously Twitter use approach 1, but system struggled to keep up with the load of home timeline queries, so company switch to approach 2. It works better because average rate of pubblished tweets is almost 2 orders of magnitude lower than the rate of home timeline reads, so in this case, it is preferable to do more work at write time and less at read time.

However, approach 2 do lots of extra work at posting a tweet. ex: a tweet is delivered to about 75 followers, so 4.6k tweets per second become 345k writes per second to the home timeline caches. Think about if user have million followers. In the example of Twitter, the distribution of followers per user is a key load parameter for discussing scalability, since it determines the fan-out load. The application may have very different characteristics, you can apply similar principles to reasoning about its load.

Twitter moving to hybrid both approaches. Most users’ tweets continue to be fanned out to home timelines at the time when they are posted, but a small number of users with a very large number of followers(i.e., celebrities) are excepted from this fan-out. Tweets from these celebrities are fetched separately and merged with that user’s home timeline when it is read.

Describing Performance

After discussing the load, we could discuss what happens when the load increases:

- When you incrase a load parameter and keep the system resources(CPU, memory, network, bandwidth, etc.) unchanged, how is the performance of your system affected?

- When you incrase a load parameter, how much do you need to increase the resources if you want to keep performance unchanged?

In a batch processing system, we usually care about throughput - the number of records we can process per second, or the total time ittakes to run a job on a dataset of a certain size.

To online system, the most important is the service’s response time - that is, the time between a client sending a request and receiving a response.

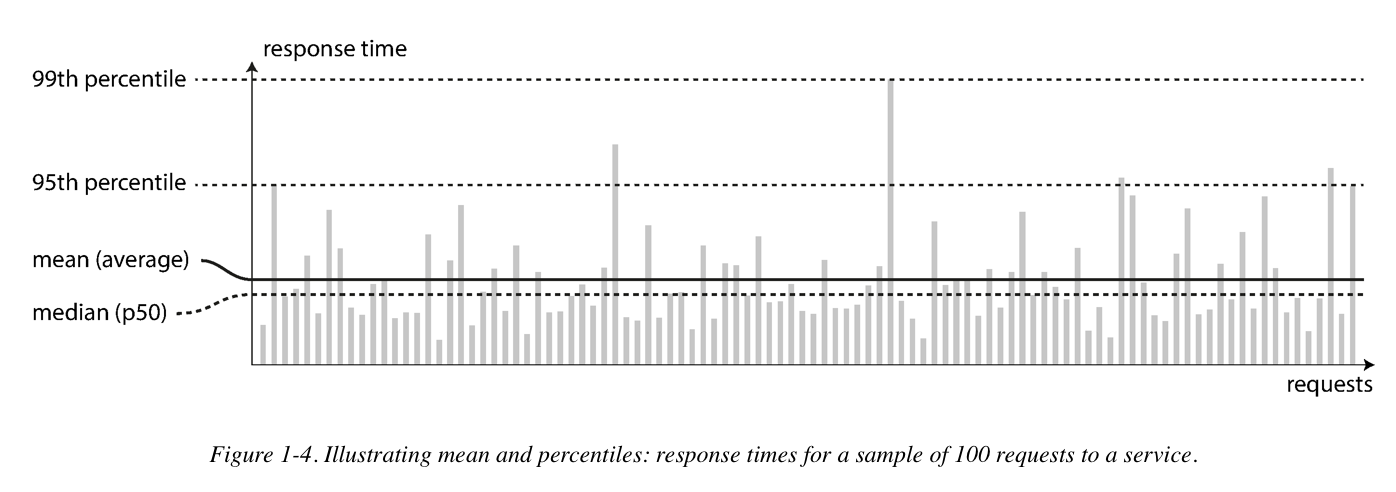

In a system handling a variety of requests, the response time can vary a lot. We therefore need to think of response time not as a single number, but as a distribution of values that you can measure.

It’s common to see the average response time of a service reported. (Strictly speaking, the term “average” doesn’t refer to any particular formula, but in practice it is usually understood as the arithmetic mean: given n values, add up all the values, and divide by n.) However, the mean is not a very good metric if you want to know your “typical” response time, because it doesn’t tell you how many users actually experienced that delay.

Usually it is better to use percentiles. If you take your list of response times and sort it from fastest to slowest, then the median is the halfway point: for example, if your median response time is 200 ms, that means half your requests return in less than 200 ms, and half your requests take longer than that.

You could also check how bad your outliers by looking at higher percentiles: the 95th, 99th, and 99.9th(abbreviated p95, p99, p99.9) are common.

High percentiles of response time also know as tail latencies, are important because they directly affect users’ experience of the service.

Example:

Amazon describes response time requirements for internal services in terms of the 99.9th percentile, even though it only affects 1 in 1,000 requests. This is because the customers with the slowest requests are often those who have the most data on their accounts because they have made many purchases—that is, they’re the most valuable customers. It’s important to keep those customers happy by ensuring the website is fast for them: Amazon has also observed that a 100 ms increase in response time reduces sales by 1%, and others report that a 1-second slowdown reduces a customer satisfaction metric by 16%

Percentiles are often used in service level objectives(SLOs) and service level agreements(SLAs), contracts that define the expected performance and availability of a service.

Queueing delays often account for a large part of the response time at high percentiles. As a server can only process a small number of things in parallel (limited, for example, by its number of CPU cores), it only takes a small number of slow requests to hold up the processing of subsequent requests—an effect sometimes known as head-of-line blocking. Even if those subsequent requests are fast to process on the server, the client will see a slow overall response time due to the time waiting for the prior request to complete. Due to this effect, it is important to measure response times on the client side.

Example:

High percentiles become especially important in backend services that are called multiple times as part of serving a single end-user request. Even if you make the calls in parallel, the end-user request still needs to wait for the slowest of the parallel calls to complete. It takes just one slow call to make the entire end-user request slow. Even if only a small percentage of backend calls are slow, the chance of getting a slow call increases if an end-user request requires multiple backend calls, and so a higher proportion of end-user requests end up being slow (an effect known as tail latency amplification).

If you want to add response time percentiles to the monitoring dashboards for your services, you need to efficiently calculate them on an ongoing basis. For example, you may want to keep a rolling window of response times of requests in the last 10 minutes. Every minute, you calculate the median and various percentiles over the values in that window and plot those metrics on a graph.

The naïve implementation is to keep a list of response times for all requests within the time window and to sort that list every minute. If that is too inefficient for you, there are algorithms that can calculate a good approximation of percentiles at minimal CPU and memory cost, such as forward decay , t-digest , or HdrHistogram . Beware that averaging percentiles, e.g., to reduce the time resolution or to combine data from several machines, is mathematically meaningless—the right way of aggregating response time data is to add the histograms.

Approaches for Croping With Load

How do we maintain good performance even when our load parameters increase by some amount?

People often talk of a dichotomy between scaling up (vertical scaling, moving to a more powerful machine) and scaling out (horizontal scaling, distributing the load across multiple smaller machines). Distributing load across multiple machines is also known as a shared-nothing architecture. In reality, good architectures usually involve a pragmatic mixture of approaches: for example, using several fairly powerful machines can still be simpler and cheaper than a large number of small virtual machines.

Some systems are elastic, meaning that they can automatically add computing resources when they detect a load increase, whereas other systems are scaled manually (a human analyzes the capacity and decides to add more machines to the system). An elastic system can be useful if load is highly unpredictable, but manually scaled systems are simpler and may have fewer operational surprises

Maintainablility

The majority of the cost of software is not its initial development, but in its ongoing maintenance - fixing bugs, keeping its systems oeprational, investigating failures, adapting it to new platforms, modifying it for new use cases, prepaying technical debt, and adding new features.

Three design principles for software systems:

- Operability: Make it easy for operations teams to keep the system running smoothly.

- Simplicity: Make it easy for new engineers to understand the system, by removing as much complexity as possible from the system. (Note this is not the same as simplicity of the user interface.)

- Evolvability: Make it easy for engineers to make changes to the system in the future, adapting it for unanticipated use cases as requirements change. Also known as extensibility, modifiability, or plasticity.

Operability: Making Like Easy for Operations

A good operations team typically is responsible for the following, and more:

- Monitoring the health of the system and quickly restoring service if it goes into a bad state

- Tracking down the cause of problems, such as system failures or degraded performance

- Keeping software and platforms up to date, including security patches

- Keeping tabs on how different systems affect each other, so that a problematic change can be avoided before it causes damage

- Anticipating future problems and solving them before they occur (e.g., capacity planning)

- Establishing good practices and tools for deployment, configuration management, and more

- Performing complex maintenance tasks, such as moving an application from one platform to another

- Maintaining the security of the system as configuration changes are made

- Defining processes that make operations predictable and help keep the production environment stable

- Preserving the organization’s knowledge about the system, even as individual people come and go

Data system can do various things to make routine tasks easy:

- Providing visibility into the runtime behavior and internals of the system, with good monitoring

- Providing good support for automation and integration with standard tools

- Avoiding dependency on individual machines (allowing machines to be taken down for maintenance while the system as a whole continues running uninterrupted)

- Providing good documentation and an easy-to-understand operational model (“If I do X, Y will happen”)

- Providing good default behavior, but also giving administrators the freedom to override defaults when needed

- Self-healing where appropriate, but also giving administrators manual control over the system state when needed

- Exhibiting predictable behavior, minimizing surprises

Simplicity: Managing Complexity

A software project mired in complexity is sometimes described as a big ball of mud. There are various possible symptoms of complexity: explosion of the state space, tight coupling of modules, tangled dependencies, inconsistent naming and terminology, hacks aimed at solving performance problems, special-casing to work around issues elsewhere, and many more.

Making a system simpler does not necessarily mean reducing its functionality; it can also mean removing accidental complexity. One of the best tools we have for removing accidental complexity is abstraction. A good abstraction can hide a great deal of implementation detail behind a clean, simple-to-understand façade. A good abstraction can also be used for a wide range of different applications. Not only is this reuse more efficient than reimplementing a similar thing multiple times, but it also leads to higher-quality software, as quality improvements in the abstracted component benefit all applications that use it.

For example, high-level programming languages are abstractions that hide machine code, CPU registers, and syscalls. SQL is an abstraction that hides complex on-disk and in-memory data structures, concurrent requests from other clients, and inconsistencies after crashes. Of course, when programming in a high-level language, we are still using machine code; we are just not using it directly, because the programming language abstraction saves us from having to think about it.

Evolvability: Making Changes Easy

In terms of organizational processes, Agile working patterns provide a framework for adapting to change. The Agile community has also developed technical tools and patterns that are helpful when developing software in a frequently changing environment, such as test-driven development (TDD) and refactoring.

Summary

An application has to meet various requirements in order to be useful. There are functional requirements (what it should do, such as allowing data to be stored, retrieved, searched, and processed in various ways), and some nonfunctional requirements (general properties like security, reliability, compliance, scalability, compatibility, and maintainability).

Reliability means making systems work correctly, even when faults occur. Faults can be in hardware (typically random and uncorrelated), software (bugs are typically systematic and hard to deal with), and humans (who inevitably make mistakes from time to time). Fault-tolerance techniques can hide certain types of faults from the end user.

Scalability means having strategies for keeping performance good, even when load increases. In order to discuss scalability, we first need ways of describing load and performance quantitatively. We briefly looked at Twitter’s home timelines as an example of describing load, and response time percentiles as a way of measuring performance. In a scalable system, you can add processing capacity in order to remain reliable under high load.

Maintainability has many facets, but in essence it’s about making life better for the engineering and operations teams who need to work with the system. Good abstractions can help reduce complexity and make the system easier to modify and adapt for new use cases. Good operability means having good visibility into the system’s health, and having effective ways of managing it.

There is unfortunately no easy fix for making applications reliable, scalable, or maintainable. However, there are certain patterns and techniques that keep reappearing in different kinds of applications. We will discuss this in later posts.

Reference

https://www.amazon.com/Designing-Data-Intensive-Applications-Reliable-Maintainable/dp/1449373321

Comments

Join the discussion for this article at here . Our comments is using Github Issues. All of posted comments will display at this page instantly.